Climate change is pushing birds higher.

June 12, 2025Protected Areas Under Pressure: Conservation Risks Falling Behind

by Riccardo Alba

Mountain areas are among the most precious and fragile biodiversity hotspots globally, hosting unique species adapted to harsh climatic conditions and extreme environments. However, a recent study conducted along an altitude gradient in the Western Alps highlights how protected areas, while essential for the protection of mountain fauna, are experiencing increasing pressures related to climate change and land use changes, which have repercussions on mountain biodiversity.

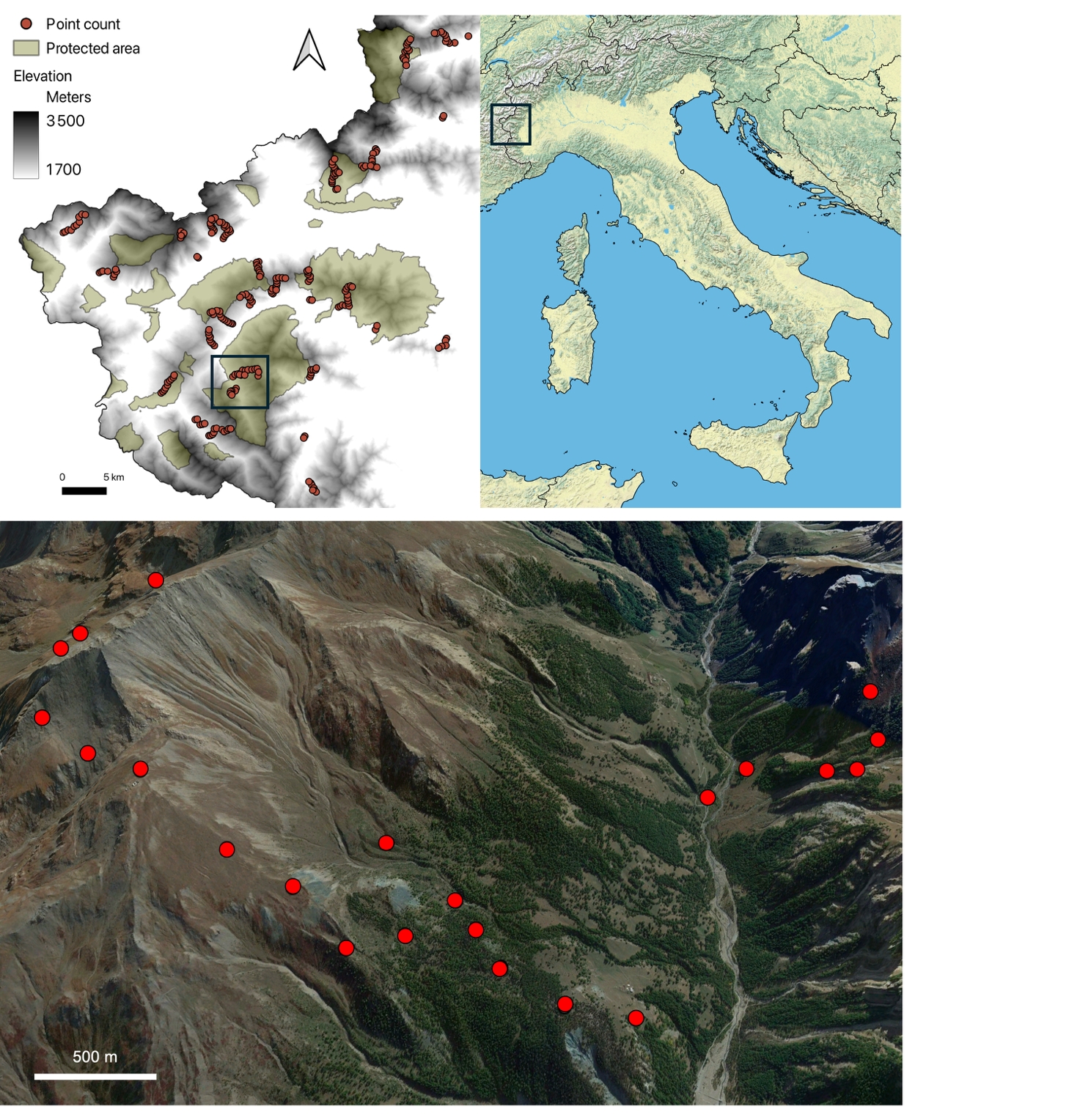

The study, conducted with Professor Dan Chamberlain from the Department of Life Sciences and Biological Systems at the University of Turin and published in the prestigious journal Biological Conservation (read the full scientific article), reports on how alpine bird communities have changed over more than a decade (2010-2023), focusing on dynamics within and outside protected areas. The altitude transects involved several protected areas in Piedmont, including some managed by the Management Body of the Protected Areas of the Cozie Alps: the Orsiera Rocciavré Natural Park, Gran Bosco di Salbertand, and Val Troncea, as well as the Natura 2000 sites Rocciamelone and Champlas - Colle Sestriere. Using the Community Temperature Index (CTI), an indicator that measures the thermal tolerance of species present in a given territory, the researchers highlighted a concerning phenomenon: while the CTI outside protected areas remained stable, it increased rapidly within them.

This trend suggests that bird communities within protected territories are changing, with a gradual decline of species specialized to the climatic conditions of high altitudes in favor of more common and thermophilic species colonizing higher altitudes. It can be assumed that at the beginning of the study (2010, 2011, 2012) protected areas were better able to host species adapted to cold climates due to the higher ecological quality of their environments. Outside, human pressure coupled with a more impactful land use (recreational activities such as skiing) had already resulted in an increase in CTI. At the time of the second survey (2022, 2023), the differences in CTI leveled off with a noticeable increase inside protected areas, while remaining stable outside. The most significant changes were observed at the upper forest limit, where shrub and forest vegetation is advancing due to warming and the abandonment of traditional pastoral activities. Furthermore, the study highlights that during the same decade there was an increase in average annual temperatures exceeding 1.19°C (Arpa Piemonte data).

Species such as the blackcap, the yellowhammer, and the wren are moving rapidly, colonizing ever higher elevations. Even species typical of coniferous forests like the coal tit have undergone significant upward shifts, as have those tied to the tree line, such as the hedge accentor. More concerning is what is happening to species like the meadow pipit or the wheatear, adapted to high-altitude habitats like alpine meadows, which do not have higher territories to migrate to, leading to the phenomenon known as “escalation towards extinction.”

Thus, the simple establishment of protected areas with fixed boundaries no longer seems sufficient to ensure the conservation of the most sensitive alpine habitats and the species that inhabit them. The ongoing environmental pressures instead require more dynamic and adaptive management strategies since the habitats and the species associated with them are continually changing. The study proposes interventions such as targeted grazing to contain forest expansion, conservation and restoration of altitude connectivity between different habitats, and continuous and intensive standardized monitoring of mountain bird communities.

These animals represent excellent bioindicators of the health status of mountain ecosystems: observing their changes allows us to gain valuable insights into the evolution of habitats and the ongoing environmental impacts. Moreover, to ensure effective and lasting conservation of alpine biodiversity, it is essential to establish active collaboration with local communities, involving them in the management and protection of the territory. Only a shared approach can ensure that mountains maintain their biodiversity, avoiding irreversible decline and preserving it for future generations.

You might also be interested in...

- campaign The migrations of ibexes and climate change

- campaign Monitorare gli ortotteri: una sperimentazione nei Parchi Alpi Cozie

- tactic MonITRing

- campaign The Alpine Carabid in the IUCN Red List

- campaign The Anthocharis euphenoides beyond yellow

- campaign Two days of discussion on water resource management

- campaign The territorial distribution of mustelids in a study

- tactic The Protected Areas of the Cozie Alps project on iNaturalist

- tactic Progetto internazionale di reintroduzione del Gipeto sulle Alpi

- tactic Monitoraggio della Biodiversità Animale in Ambiente Alpino

Research

Research